The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time should be called the Curious Incident of a Misleading Title that has way more going on. The title suggests that the reader is going to find out about an incident involving a dog at night-time. Well, that part is true. However, whilst Christopher, the book’s protagonist, is playing a detective role to find out how the neighbour’s dog died, he stumbles upon some letters from his mother hidden away in a wardrobe. Now I hear you say: why is this important? Christopher’s dad told him that his mother had died, whereas the letters suggest she lives in London, and is totally alive. Family issues right, we all have them! If there’s one thing Christopher doesn’t like, then it’s lying. This leads to Christopher running away from home. Outraged at his father for lying, Christopher puts on his detective hat once more and pledges to find his mum.

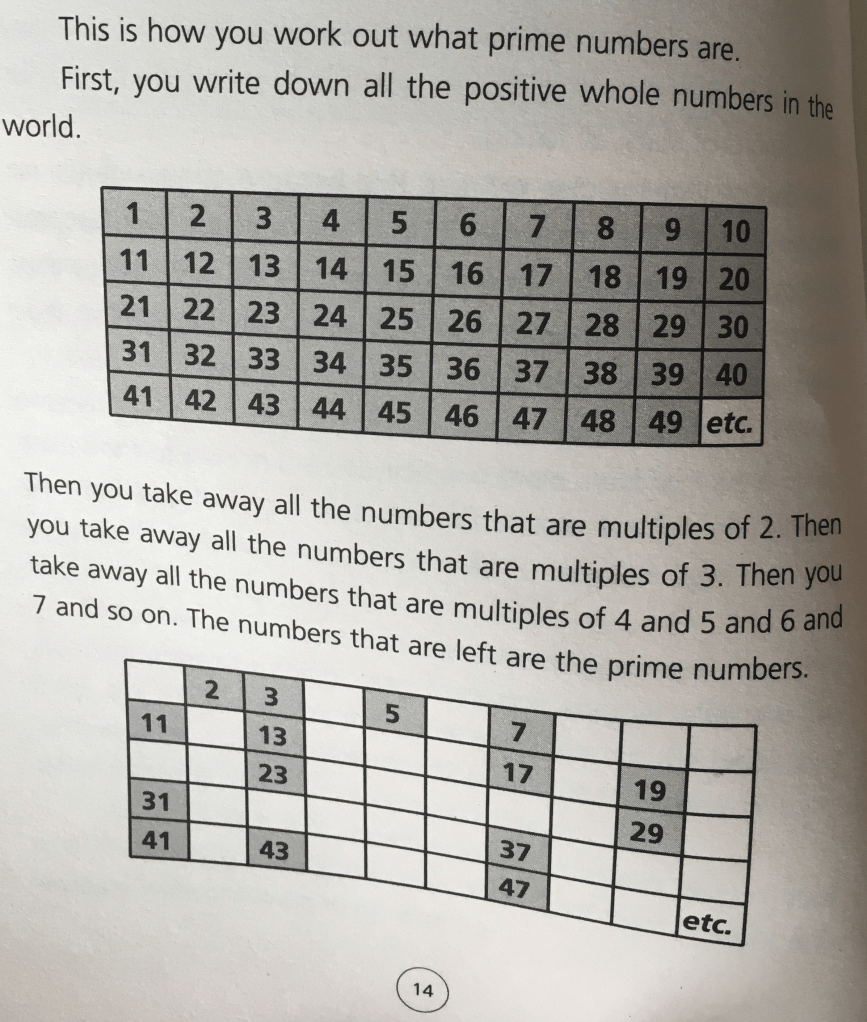

At this point in my blog, it’s probably best to mention what type of character Christopher is, as the book is written from his perspective. You see he’s not really the 15-year old boy most people would expect. He is an extremely intelligent young boy who knows “all the countries of the world and their capital cities and every prime numbers up to 7,507” (Haddon, 2004, p2). Christopher loves math because it’s logical, straightforward and has a definite answer, unlike life. Each chapter is illustrated with prime numbers, simply because Christopher likes prime numbers. He even dedicates chapter 19 to explaining how to work out what prime numbers are. But I’m not going to get into that because unlike Christopher, I hate math.

What’s interesting to note from looking at reviews about the book online is that they all mention Christopher as having Asperger’s disease or being on the autism spectrum. The only place I have read this is on the back cover of the book. Did the publishers write the summary on the back cover, or Mr Haddon himself? Now, I’m not saying that Christopher doesn’t have any of these disorders, but in the book itself I couldn’t find proof that he does. In that respect, I admire the writer for not wanting to label Christopher but instead describes him as the unique person he is.

“The word metaphor is a metaphor. I think it should be called a lie because a pig is not like a day and people do not have skeletons in their cupboards.”

Haddon, 2004, p20

The structure of the book is quite appealing. Appealing because it is different from other books: it has prime numbers, diagrams, math puzzles and smiley faces being incorporated throughout. As I’ve already mentioned, the book is written in the first person point of view, that person being Christopher. Its narration is strictly obedient: avoiding the use of metaphors, using excessive logic and paying extreme attention to detail. This, of course, reflects Christopher’s mind-set: how he views life and the colours he adopts as coping strategies.

The book, in all its glory, is packed with humour, although that usually derives from Christopher’s naivety: through his misunderstandings in situations, and his desire to be overlooked by people unknown to him. I sense that Christopher is caught in Erikson’s identity versus confusion stage. The importance of this stage is making social relationships; something that Christopher struggles enormously with. Certainly, he has discovered his own personal identity, but “how they fit in to society” is what makes teens insecure about themselves (Erikson, 1970, p4). This makes the book so appealing to the young readers, and even adults, as Christopher has challenged himself to find his mother in London. Going into a world unknown, alone! This is Christopher’s mission in making the step into adulthood. From a boy who doesn’t like to be touched, who doesn’t engage in social interactions, who has a charmingly weird way of looking at life, to an adult that can travel “about 100 miles away” and unlock his freedom to the outside world (Haddon, 2004, p164). I believe that young readers may find themselves in the same positions as Christopher, not necessarily meaning that they must go on a mission to find out who they are, rather being able to relate to Christopher feelings and struggles in making new relationships. In the book, Christopher doesn’t make friends easily; he is only close to his teacher Siobhan. Young readers may find themselves in the same situation in a particular stage of their life. They may find comfort and confidence in reading the Curious Incident.

Appleyard (1991, p6) suggests that “the adolescent turns to the realism of the book as the criterion of its acceptability”. Now here’s where my peers and I have also discussed the ‘crossover’ term. The book’s realism not only relates to young readers, but also to the adult readers. Perhaps parents reading this book can learn what not to do to their adolescents. As well as parenting skills, adults can read this book and understand the issues adolescents have when they go through a spell of uncertainty, or how adolescents may view the world differently. The book would be an enjoyable and insightful read for young 14 year olds and above. As Rees (2003) put it: the gap between adult and children’s books “has blurred almost to invisibility”. The Curious Incident unequivocally falls into its spell.

At the end of the book, Christopher gets to move back to his neighbourhood with his mother, established contact with his dad and is given the gift of a Golden Retriever. His love for the A Level Maths test waits before he dreams of going to University in another town. A happy ever after ending which begs the question: was the title descriptive after all?

Yes and yes.

Yes: if the dog hadn’t been killed, Christopher would probably never have found the letters from his mother, which set everything in motion. And the second yes: it is a title of how Christopher with his special mind would describe it, which you can only understand after reading the book.

And with that, I have successfully completed another blog. Thank you all for reading and who knows, this wanderer may have more in store in the future as the reading journey continues.

Bibliography:

Appleyard, J. A. (1991). Becoming a Reader. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Erikson, E. H. (1970). Reflections on the dissent of contemporary youth. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 51, 11-22.

Haddon, M. (2004). The Curious Incident of The Dog in the Night-Time. London, Great Britain: Vintage books.

Rees, J. (2003). We’re all reading children’s books. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/3606678/Were-all-reading-childrensbooks.html. Retrieved 5 April, 2020.